If you know the name Professor David Nutt, you probably haven’t heard it in a while. In 2009, Nutt dropped off the radar shortly after a public fall-out with high-ranking politicians. As Gordon Brown’s Drugs Adviser, his duty within this role was to make “scientific recommendations to ministers on how to classify banned drugs, based on the harm they can cause.” Yet when Professor Nutt produced the most comprehensive paper ever published to list drugs in an order based on their risk to health, this seemingly appropriate completion of the duty asked of him was instantaneously met with unparalleled opposition.

The Nutty Professor (no-one’s said that before)

The study concluded that cannabis, LSD and ecstasy are all less harmful to the public than tobacco and alcohol. Nutt had already caused controversy when he produced a paper concluding that equasy or ‘equine addiction syndrome’ causes more “serious adverse events per 350 exposures” than ecstasy, and while equasy was little more than an attempt to show how the public opinion on drugs is bias, the second paper was more serious. He argued that the lack of reliable science behind the drug policy “distorts the value of evidence” and “leads us to a position where people really don’t know what the evidence is.”

Now, Nutt is back on the scene, claiming that “absurd” drug laws “hinder research.” In his case, he claims that the difficultly in acquiring Psilocybin, the active component of magic mushrooms, has prevented research into its effects as an anti-depressant, despite preliminary results showing promising signs. Nutt stresses that the laws restricting use of magic mushrooms, ecstasy and cannabis could in fact be hindering potential advancement in medicine.

In addition, Nutt argues that the current knee-jerk response to illegalised drugs before they have been studied denies potentially effective treatments to patients and trivialises the dangers posed by known-to-be-harmful drugs such as Heroin and PCP. This has led to an attitude of self-perpetuating illegality. Because most recreational drugs are illegal, this makes it difficult to conduct any research into their effects. This further allows myths and anomalous horror stories to become falsely normalized as scientific truth, thus keeping these drugs illegal, in an ongoing cycle. This circular logic then provides well-researched drug users with a reason to believe that what they are doing is no more than harmless fun. Why would anybody trust what should be a scientific classification system, when little to no scientific evidence is used in its formulation?

despite many attempts to suppress it, it has never been conclusively shown that cannabis is harmful.

It doesn’t take a lot of searching to find that the Dr. Heath/Tulane study that has been used repeatedly to justify the illegalisation of cannabis. More importantly, the study was so full of bad scientific practice that it was impossible to accurately document any effects of the drug. Cannabis is not the only victim of bad science. An ABC news documentary revealed a similar fate for ecstasy and an even worse scientific approach to its illegalisation. Only one study conducted revealed “permanent brain damage” as the drug’s effect, using data taken mere hours after the drug had been administered. Furthermore, the study also examined the effects of N-methyl-1-phenylpropan-2-amine (crystal meth), not 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine (ecstasy). Ecstasy was seemingly illegalised due to the, at best, unreliable results from a study on an entirely unrelated drug.

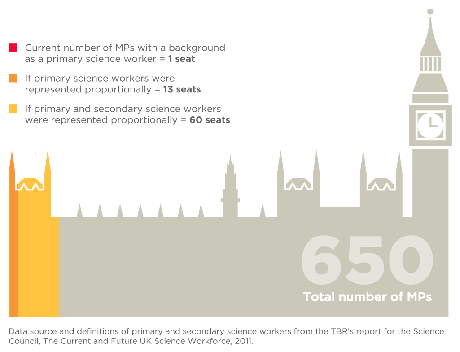

I don’t argue that ecstasy and cannabis are safe to use. But these studies also do not properly justify their illegalisation. The awful science surrounding these and other recreational drugs doesn’t allow for a reliable analysis of their effects. Without proper independent research, the true effects of a drug can never be successfully discovered. It remains impossible to decide on a proper classification for these drugs. People sometimes react in disbelief to the idea that the situation could be so bad. But when the government minister for Universities and Science is himself a PPE graduate, and only 27 of the 617 Members of Parliament have a degree in a science, why does anybody expect a scientifically sensible policy? Normally, Parliament is quite good at identifying potential gaps in knowledge and policymaking, appointing people with deeper understandings to advise MPs on legislation. But when it comes to science, it seems an adviser’s views are merely an afterthought.

A fundamental discrepancy between science and politics is found at the root of the problem. For a politician, evidence is a tool used to give views some foundation. Evidence can be interpreted in many ways, and different interpretations usually lead to drastically different conclusions. For a scientist, evidence is the most powerful weapon. It is so powerful because it can only have one conclusion, and the more times that conclusion is independently found, the more likely it is to be true. For people who have spent their entire career finding evidence which supports policy, suddenly trying to find a policy which supports the evidence must be incredibly difficult.

Education within Parliament in the differences between scientific and political evidence could potentially solve this problem. This was one of the aims of the MP pairing scheme. However, the scheme can hardly be called a success, having only attracted 180 pairings since 2001. As an optional scheme, MPs who didn’t have an interest in science—of which there are man—never signed up to it. By forcing MPs to appreciate the differences in the two types of evidence, the claims made by scientific advisers such as David Nutt might be regarded as hard scientific conclusions, rather than a personal interpretation.

Of course, this won’t singlehandedly solve the problem of bad science in the government. But it is certainly a good start. In a world where science and technology play an unavoidable role in our everyday lives, this type of reform is long overdue.

![Bad Science: Why We Need Change in Government Drug Policy If you know the name Professor David Nutt, you probably haven’t heard it in a while. In 2009, Nutt dropped off the radar shortly after […]](/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Blog-image-01_Bang-620x300.png)